Sifu Greg Brodsky is the founder of Santa Cruz Tai Chi. He wrote this in 2006

Most of the new students who come to our classes declare less interest in becoming martial artists than in gaining inner balance, a sense of peace, and improved health. They want a practice that will make them feel better and manage their lives better. Some seek healing for long standing medical problems. If they are 40 or older, they commonly report histories of physically limiting injury, surgery, or illness. These folks hope that t’ai chi can provide a sustainable, productive method for dealing with the residuals of harm to their bodies, and for cultivating well-being as the aging process becomes increasingly part of their consciousness. At the age of 64, and with considerable damage to my body, I can declare that daily t’ai chi practice helps. This article explores one aspect of t’ai chi’s method: presence of mind.

A New Language

Any effective approach to cultivating well-being must include outer work (physical, functional, interactive training and development) and inner work (mental, emotional, energetic, and spiritual discovery, attunement, training and development). T’ai chi provides all of these.

Whatever their age or level of wellness, engaging in self-cultivation requires students to learn how to use their bodies in new ways. They eventually realize that intrinsic strength is different from extrinsic strength, for example, that qi moving through the body has a unique feel to it, and that stepping with gravity relaxes them more than stepping against it. Assimilating new principles, new mechanics, and a new state of mind, it’s like learning a foreign language with ones whole body.

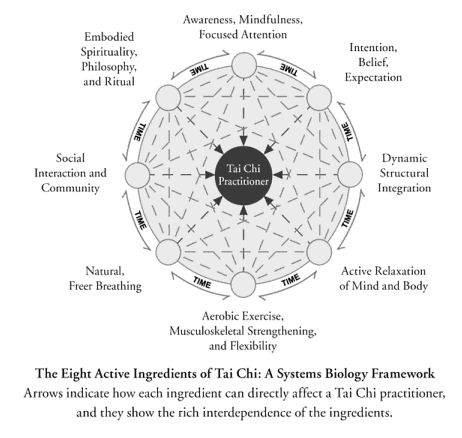

To make the t’ai chi learning process easier, practitioners historically have organized its components into addressable categories, such as: presence of mind, physical structure, mechanics of movement, breathing methods, and energetic experiences that can lead to physical healing and even spiritual transformation. The mind provides the foundational component.

It’s All In Your Mind

Human beings are habitual multitaskers. We like to do several things at once. We evolved this way for good reason, and our ability to do several things at once makes us capable of navigating the increasing complexities of the world in which we live. At the same time, life-threatening events like automobile accidents occur regularly because people fiddle with their radios, phones, hair, food, passengers, and abstract thoughts while steering one-ton vehicles through racing traffic. They arrive at t’ai chi class dragging the argument they had with their boss along with them, or the unfinished projects, frustrations, fears, and resentments of their professional lives and personal relationships. They stand there expectantly, ready to start, still sorting through the mental debris of their day, trying to calm themselves down and perk themselves up, hoping to get some peace of mind and much needed energy from practicing t’ai chi. For them, as for the rest of us, the first step in this practice is to show up. Physically showing up turns out to be the easy part. Mentally showing up—being present—proves more difficult.

Difficulties acknowledged, those who invest in presence find that the result can be supremely rewarding. Paying extraordinary attention to the immediate present frees us from the psychological burdens of our past traumas and imagined future dilemmas. Rather than regretting the past and worrying about the future, we bring ourselves into the moment. Being in the moment, our personal resources engage the real situation before us. We deal with what is there, rather than what we fear is there. Not acting on fear, we function more in accordance with our true nature and best capabilities. We also have more fun.

“All well and good,” you say, “But how does one ‘be’ in the moment?” Can a person focus the mind on what is happening both inside and outside and keep it Right Here, Right Now? There must be many simple ways to accomplish this.

What was I talking about? Oh, of course, presence. T’ai chi literature instructs the practitioner to gain presence by being intensely focused like a cat after a mouse, letting the body become loose, relaxed, and poised to move in new directions with the slightest input, and cultivating a light and agile inner spirit. This spirit manifests as serious on the outside and quietly playful on the inside. The loose, attentive state, while seemingly natural for cats and small children, typically takes years for most adults to cultivate, years that unfold one moment at a time. Being undistracted—present—for a growing number of those moments indicates something good about ones t’ai chi practice.

As a person who has struggled with his own level of presence, in my practice and life in general, I find that as an ever-useful starting point, simple sensory awareness works well. “Sensory awareness” means noticing what your senses are recording: what you see and hear right now; the temperature of the air on your skin; the moisture and warmth of your exhalations; the feeling of your body’s weight; the sensations in your back and chest and shoulders; tension and the relief of relaxing as you let gravity ground you. When we look, listen, and feel, our senses provide a doorway to presence.

Usually, I start classes with a minute or two of sensory awareness guidance, intermeshed with some reminders about alignment and looseness—gently ease the top of your head up toward the ceiling; release the kua (hip joint), knees, and ankles; loosen your shoulders, elbows, wrists and fingers; think “long spine, wide frame”—followed by some gentle warm-up breathing and movement. With a sense-heightening and self- tuning preparation, the rest of the practice becomes more satisfying. This simple opening makes it easier to become present.

Form Practice While Present

Once the form begins, ones internal awareness expands to include more of the external world. When practicing alone, this means sensing the fields in which you operate: the thick air that presses on your body to the tune of 14.5 pounds per square inch; gravity that brings you to earth and determines the meaning of “vertical alignment;” perhaps even the Earth’s electromagnetic field or the universal qi (energy) that makes the cosmos a unified thing (Only about four percent of the universe is matter, not enough for gravity to provide an explanation, yet something holds it together in a cohesive way; t’ai chi philosophy considers this “something” to be qi). T’ai chi teaches you to sense all of these. How? Pay attention. Quiet your random-access thinking and attend to your real-time experience. The quieter you are within yourself, the more you can sense.

When participating in a t’ai chi class, this is also time to pay exquisite attention to your teacher. People learn martial arts most effectively and efficiently when they treat their learning like a “monkey see; monkey do” process. The student’s job is to visually capture what the teacher demonstrates, supported perhaps by the teacher’s words, but more reliant on sight than language. A clear picture of your teacher’s movements is worth a thousand words and a dozen years.

To add context to this idea, ask yourself how your teacher will transmit what he or she has to teach you; will it be in words or deeds or simply his or her own state of being? How must you calibrate to your teacher in order to receive such a transmission?

Seeing, and later through physical contact, feeling what another person is doing enables you to calibrate to them, to tune in on their wavelength so that any kind of interpersonal transmission (communication) becomes easier. Once you align your mind with your teacher’s movement—seeing it, sensing the tempo, rhythm, quality, and specifics of your teacher’s actions, feeling the totality of his or her whole body analog (how one expresses one’s body/mind)—you can reproduce in some part what your teacher is doing. You might have only a few hours per week with a teacher, but having calibrated, captured, and learned how to recall this analog, you can have a mental representation of your teacher with you all the time.

An accurate mental snapshot of what you are doing at any moment also holds high value. Most people, in the beginning of the t’ai chi experience, don’t quite know where their body parts are in space. Are your feet parallel to each other or splayed outward? Where is your weight? You feel vertical, so why does your teacher say you are leaning? At what angle is your head? Competent placement of one’s arms, legs, and spine becomes more possible when our mind’s eye sees what we are doing.

You become better at the “monkey see; monkey do” learning process when you can jump back and forth between these two pictures frequently, quickly, and easily, using the inconsistencies between the pictures as triggers for self-correction. As your eyes go from your teacher to yourself and back to the teacher in rapid bursts, you can continually make adjustments in your position, mechanics, timing, and quality of movement. Once this becomes a habit, you find yourself continuously calibrating to your teacher through your peripheral vision. You could almost do it with your eyes closed. Almost; the key is to keep looking.

When practicing form alone, much of the looking turns inward. One can have a great deal to think about: alignment, breathing, mechanics, substantial, insubstantial, rising, sinking, opening, closing, the specifics of the movements themselves. Too much attention to detail and we can overwhelm our wonderful multi-tasking abilities; too little focus on the Now, and we can start daydreaming. Having a method to keep oneself present can prove useful. I find that sometimes a single word can provide that method.

To keep my mind from wandering, I sometimes focus exclusively on one element of the practice. Most often, the dantian (lower abdomen) holds my attention, but sometimes I “play” the top of my head, or soles of my feet, or spine, or some new sensation that I want to explore. Playing an entire round of form while never taking your mind off of single point of concentration provides quite an exercise!

When realizing that my mind has wandered, I bring myself back by silently thinking “this,” and I focus on my point of concentration. “This” is what I am doing, nothing else, no random thoughts, no conjectures, no sloppiness. Every breath, shift, and change of posture provide the opportunity to think about other things, and such wandering of thought usually occurs through an internal conversation (“…cool breeze; it might rain…how can I do this move better…wonder what’s for dinner….”). The gentle mental reminder, “This,” interrupts that conversation, bringing me back to simply paying attention to what I am doing…I am doing This.

Such attentiveness doesn’t occur exclusively through visual and verbal dimensions, though. Our attentiveness becomes more complete when we experience it as feeling as well. Whatever we perceive, and whatever ideas or principles we use to organize our actions, feeling makes it all real. Feeling enables us to experience dimensions of reality that don’t otherwise become available.

You know whether or not your t’ai chi works for you by how it feels. If the human animal within you gains well-being through your practice, you feel it. If your more primitive inner animal becomes secure enough to let you evolve sociologically, you feel that. If, through your practice, your ego gets worked in a healthy way, being calmed, tempered, and matured, your emotions tell you. When you discover a part of the path that was hidden to you before, and noticing its ramifications in your body, feel more connected to yourself and your peers, to the venerable masters who mapped the t’ai chi path, and to the universe at large, it could be that you are.

Western thinkers since the time of Descartes (“I think, therefore I am;” circa early 1600s) have considered the body and mind to be separate, but modern science challenges that separation. And, while we distinguish so-called “objective” thought from “subjective” emotions, both ancient Chinese concepts (e.g., heart-mind) and current cognitive theory recognize the unity of thought and emotions. Feeling turns out to be more than the body’s response to thought. Emotions shape the meaning and importance of what we think; moreover, they determine what we do about what we think.

When learning t’ai chi, there is no way into some aspects of the art other than feeling. Jin (internal strength), qi, stillness, alignment, sinking, rooting, emptying, and releasing, to mention a few examples, can only be experienced as feeling. You can’t explain your way into becoming quiet.

During, and at the end of your workout session, you might ask yourself what you feel. By answering this question simply and sensitively, and using the answers to adjust your routine, you can discover how to tune yourself in ways that concepts can’t achieve for you. Using your multitasking abilities to recognize your experience on more levels, ironically, you awaken a significant dimension of your presence.

Be clear about what feeling is and is not. Feeling is not analyzing. When I ask students what they feel (not how they feel), many of them want to provide an explanation or analysis of their experience: “I feel that I am less tense than yesterday,” or “I feel that I am doing a good job of remembering the moves, but that I don’t have them down yet” and so on. Rather than recognizing what they feel, they express what they think about what they feel. These opinions can be useful, perhaps, but not as a substitute for feeling.

If one pays attention to what one sees, hears, and feels, long-term practice leads to exquisite sensitivity in ones ability to feel subtle energies in ones own body, tensions and intensions in other people’s bodies, and the forces that surround us. Martial arts skills can be fun to develop and do a lot of good, but in a moment of danger, just as in a moment of learning, your presence can enable you to do the right thing.